This fact sheet was designed in support of the Collaborative Process on Indian Registration, Band Membership and First Nation Citizenship. The fact sheet provides information on the current situation or issues to ensure participants in the collaborative process can engage in well-informed and meaningful dialogues.

There are three other related fact sheets:

For a complete package of the fact sheets, please send an email to aadnc.fncitizenship-citoyennetepn.aandc@canada.ca.

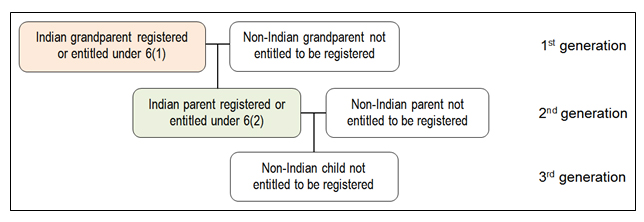

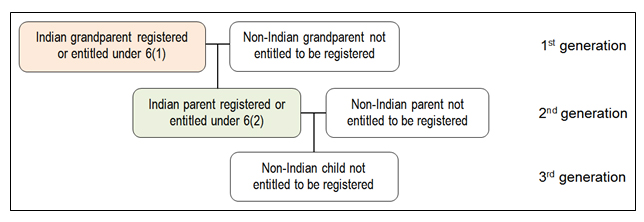

The concept of a "second-generation cut-off" was introduced in 1985 as part of the Bill C-31 amendments through the creation of two general categories of Indian registration (sections 6(1) and 6(2)) and the related ability to transmit entitlement to children. After two consecutive generations of parenting with a person who is not entitled to registration (a non-Indian), the third generation is no longer entitled to registration. Entitlement is therefore cut-off after the second-generation. In other words, an individual will not be entitled to Indian registration if they have one grandparent and one parent who are not entitled to registration. The following diagram illustrates how the second-generation cut-off is applied:

Description of Figure 1: Application of the second-generation cut-off

Figure 1 presents the application of the second-generation cut-off. In the first generation, an Indian grandparent who is registered or entitled to register under section 6(1) parents with a non-Indian grandparent who is not entitled to register. In the second generation, the offspring is an Indian individual who is registered or entitled to register under section 6(2). This individual also parents with a non-Indian parent who is not entitled to be registered. The third generation is a non-Indian child who is not entitled to be registered.

The second-generation cut-off is neutral with respect to sex, family status, marital status, ancestry or place of residence.

The Bill C-31 amendments were written to allow for a second-generation cut-off in response to concerns raised by First Nations during parliamentary debates with respect to resource pressures and cultural erosion in First Nation communities. First Nations expected a significant increase in registered individuals with no current familial, kinship or community ties. The rationale for the inclusion of this cut-off was an attempt to balance individual and collective rights with a view to protecting First Nation culture and traditions.

The application and operation of the second-generation cut-off is "mechanical." It is applied without any consideration to the individual or their family's circumstances. Under the exploratory process in 2011-2012, it was reported by some First Nation communities that some members were unfairly subjected to the second-generation cut-off even though the member and their family had always been connected to the band and community. The issue was also raised during the parliamentary debates on Bill S-3 and as a result is included as a subject matter for consultation under the collaborative process.

In addition, the second-generation cut-off is a gender neutral transmission rule for individuals born post-1985. It allows for entitlement for children under section 6(1)(f) when they have two registered or entitled parents or under section 6(2) when only one of their parents is registered or entitled. This ensures that the transmission of entitlement of status continues forward if the conditions are met. With no such rule, there would be no way for one registered parent to transmit their entitlement to children born after 1985.

Most human rights reflect an individualistic concept of rights and rights-holders. However for many First Nations people, their identity as an individual is connected to the community to which that individual belongs. Therefore the challenge is that while the charter and human rights laws guarantee individual rights, First Nations ask for protection of their collective rights as a group.

Under the Indian Act , the registration of an individual is based on genealogy and is dependent on the status of both parents. When Indian parentage is asserted in an application for registration, there may be situations where the parent, grandparent or other ancestor of the person in respect of whom an application for registration is made is unknown or unstated on birth documents. These types of situations could negatively impact a person's ability to be registered as a status Indian. The Policy on Unknown or Unstated Parentage has recently been revised.

Unknown parentage is when an individual person who is applying for registration does not know, is unable or is unwilling to provide information about a parent, grandparent or ancestor.

Unstated parentage is when an individual parent, grandparent or ancestor is known but is not listed on their proof of birth document.

As noted, under the Indian Act , the registration of an individual depends on their parents' eligibility for registration. In the case of an unknown or unstated parent, an individual with one parent registered under section 6(1) would only be eligible to be registered under section 6(2).

Description of Figure 1: Registration of an Indian child with one parent registered or entitled under 6(1) and one unknown or unstated parent

Figure 1 presents an Indian parent who is registered or entitled to register under section 6(1) and an unknown or unstated parent. The child of these parents is an Indian child who is registered or entitled to register under section 6(2).

If an individual has one parent that is registered under section 6(2) and the other parent is unknown or unstated, then they would not be eligible to be registered under the Indian Act .

Description of Figure 2: Registration of an Indian child with one parent registered or entitled under 6(2) and one unknown or unstated parent

Figure 2 presents an Indian parent who is registered or entitled to register under section 6(2) and an unknown or unstated parent. The child of these parents is a non-Indian child who is not entitled to register for status.

Having a parent, grandparent or ancestor that is unknown or unstated could result in an individual who applies for Indian status to not be entitled.

In the Gehl decision, PDF format (492 Kb, 45 pages) the Ontario Court of Appeal determined that the Indian Registrar's policy with respect to unstated or unknown parentage was unreasonable as it forced a high burden of evidence on the applicant and required the applicant to state the identity of the parent, grandparent, or ancestor, even in cases where such identity is not known. The court recognized that women were unfairly disadvantaged by the requirements of proving Indian parentage when compared to men and that a rule requiring the identification of a status parent is unreasonable because it demands evidence not required by the act. The court also found that the Indian Registrar's policy did not do enough to address situations where women cannot or will not name their child's biological father.

In response to the Gehl decision, a new provision was added to the Indian Act through Bill S-3 to address the issue of unstated and unknown parentage. The new provision, now in force, provides flexibility for applicants to present various forms of evidence. It requires the Indian Registrar to draw from any credible evidence and make every reasonable inference in favour of applicants in determining eligibility for registration in situations of an unknown or unstated parent, grandparent or other ancestor. The new policy aligns with Bill S-3 and seeks to address cases of evidentiary difficulties around unknown or unstated parentage. It provides the following rules to be applied by the Indian Registrar when considering applications for registration in situations of unknown or unstated parentage:

Prior to the Bill C-31 amendments in 1985, enfranchisement resulted in an individual no longer being considered an Indian under federal government legislation. Indians who were enfranchised were removed from their band lists before September 4, 1951, or lost Indian status if enfranchised after September 4, 1951. When an individual was no longer considered an Indian, the individual lost all associated benefits that resulted from being on a band list (pre-1951) or a status Indian (post-1951). It also meant all their descendants were not considered Indian and could not obtain any related benefits. This impact is still felt by current generations.

Prior to Bill C-31, there were three ways Indian men, women and children could be removed from a band list or lose Indian status through enfranchisement.

When a woman was enfranchised due to marriage to a non-Indian man, any children she already had, or would have, were considered non-Indians. When a man enfranchised, his wife and children would also be enfranchised.

Enfranchisement as described in items 1 and 2 above was considered involuntary, meaning that enfranchisement occurred without the consent of the persons concerned. Item 3 above was considered voluntary. This was done by application where Indian men or women had to prove they were "civilized" and able to take care of themselves without being dependent upon the government. This process included submitting a report and getting approval from their band. If all the requirements were met, they would receive a letter (called letters patent), that declared them enfranchised and no longer Indians.

Individuals who enfranchised received the same rights and benefits that existed for non-Indian Canadians. In addition to these rights and benefits, there were a number of benefits that were made available to an enfranchised individual and their family through previous versions of the Indian Act .

From 1869 to 1951, an enfranchised individual could receive land compensation by being provided a portion of the band's land to take care of. An enfranchised individual would have three to five years to prove he was able to be independent. If successful, the enfranchised individual would own the land. From 1951 to 1985, land continued to be available to enfranchised individuals by making compensation to the band.

Financial compensation would also be provided to enfranchised individuals. From 1876 to 1985, enfranchised individuals received a percentage (or per capita) payment of what their band would have received from the government. From 1951 to 1985, when a Treaty Indian enfranchised, they would receive an amount equal to twenty years of treaty payments.

Enfranchisement had an impact on all subsequent generations of people. Regardless of whether an individual was voluntarily, or involuntarily enfranchised, subsequent generations could not appear on band lists or on the Indian Register as a status Indian.

Bill C-31 removed both voluntary and involuntary enfranchisement provisions. Individuals who enfranchised, along with their children, could be reinstated or became eligible for registration.

The 2017 amendments (Bill S-3) corrected sex-based inequities for women, and their descendants, when the woman involuntarily lost entitlement to registration due to marriage to a non-Indian man. Bill S-3 brings entitlement to descendants of women who married a non-Indian man in line with descendants of individuals who were never enfranchised. However, the descendants of individuals who were enfranchised for other reasons (both voluntary and involuntary) remain at a disadvantage in comparison. These remaining inequities within the Indian Act continue to have an impact.

It should be noted that the second-generation cut-off is distinct from the issue of enfranchisement and generally for individual born after April 17, 1985, the second-generation applies. Consult the fact sheet on Second-generation cut-off.

Deregistration, if implemented, would be the act of removing the name of a registered individual, at their request, from the Indian Register and from a band list maintained in the department if applicable. Once deregistered, an individual would lose access to services and benefits associated with Indian status but their entitlement to registration would remain (or would continue to exist).

For First Nations who fall under section 11 of the Indian Act where the Indian Registrar maintains their band membership list, the individual would also be removed from the membership list. For First Nations that control their own membership lists under section 10 of the Indian Act or under self-government type agreements, it would be up to the First Nations to determine what happens for that person who has requested to be removed from the Indian Register (deregister).

Deregistration is not the same as enfranchisement. Deregistration, if implemented, would involve an individual requesting to have only their name removed from the Indian Register, but would maintain their entitlement to being registered without impacting subsequent generations. Enfranchisement was the process of removing from an individual their entitlement to registration affecting the entitlement of all subsequent generations.

There is currently no provision in the Indian Act to remove a person who is entitled to be registered as an Indian and who wishes to be removed from the Indian Register. The 1985 Bill C-31 Indian Act amendments struck out the means to remove someone from the Indian Register who is entitled under the Indian Act . The Registrar can only remove someone who is not eligible for registration, regardless of the reason for wanting to deregister.

Since 1985, many individuals have expressed a desire to be removed from the Indian Register for a variety of reasons, including:

The Peavine-Cunningham Supreme Court decision ruled that members of the Métis settlements cannot hold Indian status if they wish to maintain their Métis status under the provincial legislation in Alberta. Some other Métis groups and American Tribes have shaped their membership definitions and rules to exclude those who are registered as Indians under the Indian Act .

Since entitlement to registration is determined by genealogy or lineage, there is a legislative need to record birth-assigned sex in the Indian Register. Registration currently only refers to sex as identified on official proof of birth documents and does not account for gender identity, especially when it may differ from an individual's recorded sex designation as male or female. The sex indicated on the application forms for registration as a Status Indian or for the Secure Certificate of Indian Status (SCIS) must match the sex indicated on an applicant's proof of birth document.

Applicants who wish to be registered under a different sex based on their gender identity are required to amend their proof of birth document prior to registration. Sex is currently listed on the SCIS based on the information recorded in the Indian Register. Status Indians who wish to change the sex on their Secure Certificate of Indian Status must apply for an amendment and provide the required supporting documentation.

Culturally defined roles, behaviors, activities and attributes associated with males and females are known as gender. Gender identity is each person's internal and individual experience of gender, while gender expression is the public presentation of that identity through behavior and appearance. A person's gender identity or expression may be the same as, or different from, the biological and physical characteristics that designate a person's birth-assigned sex.

A cisgender person identifies with the gender traditionally associated with their birth-assigned sex. For example, a cisgender woman is born female and identifies with the female gender.

A gender diverse person may identify with the gender associated to the "opposite" sex, a combination of genders, or no gender identity.

Transgender is an umbrella term that refers to people whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. A transgender person may or may not have sought gender affirmation surgery. A transgender person may have diverse gender identities and expressions that may differ from societal expectations. There are a wide range of terms on the gender spectrum such as non-binary gender, gender-queer, gender variant, gender non-conforming, gender neutral, agender.

Under Bill C-16, legislative amendments to the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code now recognize gender diverse people. An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code came into force on June 19, 2017 adding gender identity or expression to the prohibited grounds of discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code definition of identifiable groups.

As it is currently written, the Indian Act does not have provisions that specifically address gender diverse or transgender people. Under Bill S-3, amendments came into force on December 22, 2017 to eliminate sex-based inequities in Indian registration under the Indian Act . These amendments are gender neutral and apply equally, regardless of gender identity or expression, in accordance with the recent amendments to the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code .

Registration under the Indian Act is a key part of Canadian legislation affecting Indigenous people and impacts eligibility for certain programs, such as extended health benefits, post-secondary education funding and exemption from certain provincial taxes. The collaborative process allows an opportunity to have discussions and collect information around gender identity in Indian registration.

Interdepartmental discussions are also taking place using Gender-Based Analysis.

The number of same-sex couples has grown considerably in Canada over the past 10 years. The percentage of same-sex couples with children has increased as well. Same-sex couples often face obstacles to having children that may require outside assistance like adoption or medical technology to aid conception. This can lead to issues around the recognition of both same-sex parents on a birth certificate or in some cases, recognition of more than two parents for a child (biological and adopted). Currently, parental rights and recognition vary by province or territory.

Determining Indian status for children of same-sex parents involves looking at both the biological parents and adoptive parents. For children of same-sex couples, there are a number of combinations of parents that may be present in their life. At least one parent, either adoptive or biological, must be registered or entitled to be registered under section 6(1) under the Indian Act in order for the child to be entitled to be registered. See fact sheet on Section 6(1) and 6(2) registration.

Currently, there are administrative obstacles for children of same-sex parents when applying for registration as some forms require the applicant to provide their father's family name and their mother's maiden name. For same-sex couples and their children, these forms requirements may enforce parental relationships that do not exist or do not apply to their situation.

Applications received from children of same-sex parents are assessed on a case-by-case basis.

The Canada-United States border can pose challenges for members of many Indigenous communities, with implications for their daily mobility, traditional practices, and economic opportunities as well as for their family and cultural ties with Native Americans from the United States. Border crossing issues were the subject of a 2017 engagement process undertaken by a federal Minister's Special Representative with many concerned First Nations communities across Canada, from Yukon to New Brunswick.

Drawing on meetings with representatives from more than 100 First Nations, the Report on First Nation border crossing issues identifies seven key sets of border crossing challenges. These include issues relating to registration, membership, identity and identity documents. The report also touches upon mobility rights, the Jay Treaty, immigration laws, and the experience of crossing the border at ports of entry administered by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA).

A feature to Canadian immigration legislation since the 1976 Immigration Act is the explicit recognition of a right of entry to Canada for First Nations people registered under the Indian Act , regardless of whether or not they are Canadian citizens.

Under section 19 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act , individuals able to satisfy a CBSA officer that they are registered Indians may enter or re-enter and remain in Canada. The Secure Certificate of Indian Status (SCIS) and the Certificate of Indian Status (CIS) are documents that the CBSA accepts to establish one's right of entry on the basis of registered Indian status.

For its part, the United States (US) explicitly recognizes a right of entry to the US, for the purposes of employment and residence, to "American Indians born in Canada." This right is conditional upon an individual being able to demonstrate that, they "possess at least 50 % of blood of the American Indian race", under the terms of the US law.

As a matter of policy, the US accepts the Secure Certificate of Indian Status and the Certificate of Indian Status issued by the Government of Canada in partnership with First Nations, as documents that registered Indians from Canada may present to enter the US by land or by sea.

As noted in the report on border crossing issues, Canada's immigration laws and the Indian Act can present challenges for communities with close family, cultural and historical ties with Native American Tribes in neighboring US states. For example:

A committee of senior officials from concerned federal departments has been carefully reviewing the Ministerial Special Representative's report on border crossing in order to make recommendations to the government on next steps that might be taken in partnership with First Nations and other Indigenous communities to address their border crossing concerns.

Following consideration of the recommendations of the committee of senior officials, the government will re-engage with First Nations and other Indigenous communities to discuss next steps in addressing their border crossing issues.

According to the Government of Canada, there are three recognized types of adoption in relation to registration under the Indian Act .

| Legal adoption | Custom adoption Footnote 1 | De Facto adoption |

|---|---|---|

| An adoption under provincial or territorial adoption laws, including private adoptions through an accredited third party. May include international adoptions if the agency is recognized by a Canadian authority. | A clear parent-child relationship is established with all the related legal, financial and other benefits and burdens of an adoption, but that is not processed according to provincial or territorial adoption laws | Where a child has been in the care of the adoptive parent or parents but the legal adoption happens after the person is an adult |

Under 1985 amendments to the Indian Act , the definition of a child includes a legally adopted child and a child adopted in accordance with Indian custom.

Adoptees must have been a minor at the time when they were taken under care. Adoptees may be eligible for entitlement to registration under the Indian Act, either through their birth parent(s) or through their adoptive parent(s). At least one parent, either adoptive or birth, must be registered or entitled to be registered under section 6(1) of the Indian Act for the adoptee to be entitled to be registered. See fact sheet on Section 6(1) and 6(2) registration.

The Indian Registrar will make the decision most in favour of the applicant based on either their birth or adoptive parent(s) to facilitate registration entitlement for subsequent generations.

For adopted individuals, there is the choice to be registered with a connection to the band of their adoptive parent(s) or their birth parent(s), if known. The different adoption types have different document requirements when applying for registration. All types of adoption are considered for registration under 6(1) and 6(2).

To be registered following a custom adoption, the applicant must submit documentation signed by a band council and Elders of the band stating that the adopted individual was adopted and raised in accordance with the customs of the band of the adoptive parent(s) to ensure a connection to the community and culture where the adoption is not considered a legal adoption. Other documentation may be required along with the application form, including:

Adoption is not defined in federal law. It is currently under the jurisdiction of provinces and territories, meaning the terms can vary across the country. This could be challenging when applying for Indian status for adoptees that must adhere to the adoption laws of their province or territory.

This is Canada's definition of custom adoption, which may not be the same in all First Nation communities.

Thank you for your feedback